Charters of Liberties from Crown of England to Guernsey and Jersey from WIKI & GovernmentThe Seigneur of Fief Blondel, Chancellor George Mentz, JD MBA OSG, wishes King Charles III "The Duke of Normandy" and the Queen a wonderful visit with the people and Seigneurs and Dames of Guernsey. King and Queen to visit Guernsey next month July 2024 | Guernsey Press Royal charters applying to the Channel IslandsThis is a list of charters promulgated by Monarchs of England that specifically relate to the islands of Jersey, Guernsey, Alderney or Sark which together form the Channel Islands, also known as the Bailiwick of Jersey and the Bailiwick of Guernsey. Forming part of Brittany and then Normandy in the 10th and 11th centuries,

the Duke of Normandy, in 1066, took the

Crown of England. The physical location of the Channel Islands became important when the English Monarchs began to lose their French possessions and the islands became the front line in a series of wars with France that lasted for centuries. Loyalty to the English Crown was rewarded. The Charters are given in the form of Letters patent being a form of open or public proclamation and generally conclude with: In cujus rei testimonium has literas nostras fieri fecimus patentes. (in witness whereof we have caused these our letters to be made patent.)[1] : 42–44 The Charters being confirmed by the Council in Parliament, or by the Parliament of England.[2] Lord Kinnear, in Smith v. Lerwick Harbour Trustees said about the Crown's property rights: "If the solum of Shetland as a whole is not originally the property of the Crown, I know of no authority, and can see no reason, for holding (saying) that part of it which is called the foreshore is Crown Property". This statement could equally well be applied to the seabed, especially since the foreshore is regarded as part of the seabed in English law. S.O.U.L. (udallaw.com) The legal materials are as follows:

References

Jersey & Guernsey Law Review – June 2009Jersey’s royal charters of libertiesTim Thornton1 The series of charters of liberties granted to Jersey, some just to the Island, others jointly with Guernsey and its Bailiwick, do not simply repeat each other. The sequence of documents, spanning the years from the middle of the 14th century to the end of the 17th, demonstrate the continuing concern of the English Crown for the Island’s liberties. In the 1390s, exemption from tolls and dues in England was added, and then in the 16th century Edward VI confirmed the freedom of trade in times of war which had previously relied on papal sanction. Much more specific itemisation came in a charter of Elizabeth I, referring to the jurisdiction of Bailiff, Jurats and others, and to the right to justice within the Isle without having to seek further afield. 2 The charters of liberties reveal more than this, however, reflecting attitudes to the Islands, and the context of royal power which created them. They should also be seen in terms of their limits, for example in the ways in which they intersected with ongoing English efforts to control the ability of Jersey merchants to trade in and out of England without regard for the Staple (which regulated the wool trade) or other restrictions. In 1410, reports of exports of tin to La Rochelle, Normandy and elsewhere in France brought efforts to control their activities in Cornwall.[1] In 1469, soon after the French occupation of Jersey ended, another example of this control, specifically now to allow exports of up to £2000 worth of goods, was passed.[2] 3 More than a century after the separation of Jersey from Normandy consequent on the failures of the reign of King John, the first confirmation of the Island’s liberties was granted by Edward III in 1341. The customs of the Island had been documented over the previous century for example through royal inquests, as in 1247 and 1248, and in quo warranto proceedings such as those of 1309. They provided that the Island would not be governed by the law of England or that of Normandy, but by a distinct set of political, social and economic rights and duties which defined the status of the inhabitants and guaranteed the whole through the participation of the Jurats in the judgments given out by the king’s courts in the Island, and exempted the people of Jersey from summons to a secular court elsewhere.[3] However gloriously the English King might later have triumphed in the Hundred Years’ War, Edward III’s fortunes in the immediate aftermath of his claim to the French throne were not great. In 1336 and 1337, supported by the French, the exiled claimant to the Scottish throne, David Bruce, raided Jersey and Guernsey, and in 1338 Guernsey was occupied by the French. It was not until the autumn of 1340 that the Island was retaken by the English, while Castle Cornet was held by the French for seven years.[4] Edward had formally declared his claim to the French throne in 1337 and launched his first attack on France in 1338. English armies on the continent of Europe were, however, notably unsuccessful, and Edward faced difficulties at home too, with resistance in Parliament in 1340 and 1341.[5] It was only in the spring of 1341, with the death of John III of Brittany, that Edward perceived an opportunity that might be seized, supporting John’s half-brother John de Montfort against the alternative claimant Charles of Blois, who was married to Joanna, heiress of Duke John III, and who was the son of Margaret of Valois, sister of Philip VI of France.[6] Many years before, in 1331, the communities of Jersey and Guernsey had been summoned to explain by what right they enjoyed their liberties and responded vociferously if not violently in their defence, in a case for which, unfortunately, we have no recorded outcome. In July of 1341, as opportunity beckoned for the king, Edward confirmed the privileges of both Jersey and Guernsey, and the latter’s associated Islands. He called to mind particularly the faithfulness of the Islands’ communities, and the dangers they had undergone. [7] 4 Richard II confirmed his grandfather’s charter in 1378.[8] This was a relatively unexceptional confirmation, although, after the years of English military success in the middle years of Edward’s reign, Richard’s regime was finding itself as its predecessor had in 1341, under great pressure as the Brétigny settlement was effectively challenged by the French. With most of Brittany having been under French domination for some years, there was no question but that, once again, the English King needed the support of the Island communities.[9] More significantly, however, in June 1394, Richard extended the previous grant by adding for the Islanders an exemption from tolls, duties and customs in England, as if they were English.[10] Richard’s policies of reliance on non-English territories, to which he granted extensive privileges, are now well known, and in a small way Richard involved the Islands as part of this policy, investing in them as a base for the Earl of Rutland, one of his favourites, and using them as a prison for one of his enemies, John, Lord Cobham.[11] 5 Henry IV, seizing Richard’s throne, did not confirm Richard’s grant of exemption from tolls, duties and customs of 1394, limiting his charter (of May 1400) to a confirmation of that of Edward III, as Richard’s first charter to the Islands, of 1378, had done.[12] It may be that the experience of John, Lord Cobham, exiled to Jersey by Richard, and active in the Parliament of 1399 which dealt with Richard’s allies, told against the continuation of the notable privilege exempting the Islanders from tolls, duties and customs in England.[13] Henry, too, was cautious in his resumption of hostilities with France, and so without the urgent need of the strategic advantages of the Islands.[14] 6 Henry V in 1414[15] and Henry VI in 1442[16] reconfirmed in turn Henry IV’s confirmation of 1400. The context for these confirmations was the French war, and the fate of the lordship of the Islands. In 1414, Henry V was still at peace with the French, apparently seeking a treaty for the marriage of the French King’s daughter Catherine, a substantial dowry, and extensive lands. He was also working to continue a truce with the duke of Brittany, with Guernsey the site for a meeting between the commissioners of each side.[17] But in 1415, soon after the confirmation of the Islands’ privileges, he was at war, and hostilities continued beyond his death. By 1442, however, his son Henry VI was showing increasing signs of an interest in the termination of the conflict. The Islands’ position was particularly sensitive in this connection: their lordship had been granted to the new King’s uncle, John, Duke of Bedford, and on his death John’s younger brother, Humphrey, was successful in petitioning for them.[18] Humphrey was, of course, a vigorous advocate of the continuation of the French war. The innovation of the 1442 charter was to introduce, as well as the confirmation of the charter of 1341, a confirmation of the previously ignored grant of 1394 by Richard II. We might consider the reasons for this—the gradual rehabilitation of Richard II, even under the Lancastrians;[19] the advocacy of a lord of the Islands who might have valued their prosperity as a factor in his aggressive stance; and, more defensively, a recognition of the weakness of the English position in France amidst a new mood at court favourable to gestures of peace. 7 The next charter in the sequence represents something of a discontinuity. The first element to this break was due to the seizure of Jersey from its governor, John Nanfan, by the forces of the Comte de Maulevrier in 1461 Neither Bailiwick received any confirmation of privileges for several years, as the occupation of Jersey continued. Then, in 1465, Edward granted a charter confirming both of Richard II’s charters to Guernsey, Alderney and Sark alone, recognising the reality of the separation of the Bailiwicks consequent on the occupation by the forces of the Norman Jean de Carbonnel.[20] When Jersey was recovered by the English crown in 1468, on 28 January 1469 Edward confirmed specifically to Jersey the Island’s liberties granted in Richard II’s second charter of liberties, and extended this for the first time with an exemption from tolls, pontages, subsidies etc. This confirmation made special reference to the exertions of its inhabitants in assisting in the recapture of Mont Orgueil and of Jersey.[21] 8 The other discontinuity was one of dynasty. Edward IV viewed the Lancastrian monarchs as illegitimate—the consequence of the interruption to legitimate succession resulting from the usurpation of Henry IV of 1399. There were many signs of this, amongst them his charters of liberties for the Islands. Determined to break from the tradition of confirmation and reconfirmation seen under his predecessors, Edward returned to the charters of Richard II, omitting the previous 70 years of history. It was not the charters of 1400, 1414, and 1442 which were confirmed; Edward’s charter returned to Richard II’s concession of exemption from tolls, duties and customs.[22] 9 When Richard III came to confirm the privileges of the Bailiwicks, he too conducted an intriguing exercise in overwriting the events of the previous reign. His confirmation took the form of a confirmation of the charter of 1465, which of course had been issued only to Guernsey, but it silently amended the record to make the confirmation one to both Guernsey and Jersey.[23] It may be that this choice of the 1465 charter represented a rejection of the implications of the charter of 1469, issued at a time when the lordship of the Islands had passed away from the influence of Richard’s father-in-law, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, to that of the Woodvilles, his rivals for power in the chaotic days after Edward IV died.[24] 10 Henry VII confirmed each Island’s privileges separately, and intriguingly differently. His confirmation to Guernsey, Sark and Alderney was a confirmation of the 1469 charter of Edward IV, on 10 February 1486; on the same day he confirmed Jersey’s privileges, referring directly back to the grant of Richard II, then following the wording of the grant to Guernsey and its Bailiwick.[25] This confirmed the excision of Richard III from the record, as it did the disappearance of the Lancastrian Kings. Henry was definitely in this case the successor of his father-in-law Edward IV, and the restorer of the unity which had been lost on the death of Richard II. As in other aspects of Henry’s government of the Islands, treated separately for the first time,[26] it returned to a position of separate charters for each Bailiwick. 11 In 1510, Henry VIII confirmed his father’s inspeximus and confirmation to Jersey, in the charter of 26 February 1510. This took the form of a confirmation of a charter of Henry VII confirming the charter of 1469, itself confirming the Richard II charter—in practice, therefore, using the text of the Guernsey confirmation of his father, rather than that of the Jersey one, albeit making it refer specifically to Jersey.[27] 12 Edward VI’s charter to Jersey was innovative in several respects.[28] It returned to the tradition of granting privileges jointly to both Jersey and to Guernsey and, in a sign of the impact of the Reformation and of his regime’s Protestant nationalist outlook, it incorporated a statement of the Islands’ neutrality, something for which since the 1480s they had relied on a papal bull. Edward’s charter refused to recognise any papal involvement in the establishment of neutrality, choosing instead to refer vaguely to “various other privileges not expressed in the letters ... conceded by our progenitors”. 13 Initially Edward’s charter to both Bailiwicks confirmed the charters of Henry, his father, and of Henry, his grandfather (both specifically to Jersey), and of Edward, his great-grandfather (20 January 1469, to Jersey), ultimately confirming that of Richard II to both Bailiwicks in 1394. That done, the charter called to mind the bravery of the Island communities in their defence of Mont Orgeuil, apparently in reference to the much earlier events of Edward IV’s reign, indicating that this was on the advice of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset and the King’s uncle and protector, a man with a record of interest in the Islands since 1536.[29] The reward for this loyalty was to be not just the freedom from tolls and customs which (along with duties) were specified by Richard II’s charter, but also subsidies, and the dues of pontage, pannage, murage, and fossage, relating to the use of bridges, woodland pasturage, and the maintenance of town walls, and ditches, respectively. There was then a confirmation of all the liberties and franchises which any of them had before enjoyed. The charter then became specific in reference to two exactions on the people of Jersey, one recently imposed and the other customary—the first on wheat exports, the second on wool exports, which were regulated from an alleged rate of 3s 6d per quarter and 4d per 150 pounds weight, to 12d and 3s 6d respectively. 14 The latter measure shows one clear sign of the origins of the charter. This is an undated petition of the inhabitants of the Islands to Somerset, which ends with a call for the ending or mitigation of the custom on wheat exports. The petition also refers to free access and trade for all merchants coming to the Islands, even in time of war. Both these requests being granted, however, there were others which were not acceded to: issues relating to royal lands, to partible inheritance, repair of ports, for the Captain, Bailiff, Dean and others to decide petty causes, and to writs and commissions from chancery.[30] 15 In a sign of the lack of alignment between her regime’s priorities, especially in the religious field, and the Jersey community, the reign of Mary saw no confirmation of Jersey’s privileges entered on the Patent Roll. In Guernsey, where Roman Catholic restoration was more readily welcomed, and where the governor, Peter Mewtas, had been a stalwart of the Northumberland regime which the new Queen, effectively, overthrew, Mary abandoned the innovations to the form and content of the charters of liberties made by her brother, granting a confirmation of the charter of her father, Henry VIII, and therefore granting specifically to Guernsey.[31] In Jersey, however, there was silence, as her regime seems to have tolerated a continuation of the regime of Sir Hugh Paulet, who with many leading families was an adherent of Protestantism, in the interests of security in the face of a French threat to both Bailiwicks.[32] 16 While in Guernsey Elizabeth soon confirmed, simply and straightforwardly, the charter of her elder half-sister, following it in 1560 with a much more distinctive document;[33] in Jersey it was not until 1562 that a charter of confirmation was granted.[34] This mirrored very closely the document granted to Guernsey in 1560. As in the Guernsey charter, the 1562 charter confirmed Jersey’s exemption from English customs and duties, and reaffirmed neutrality and freedom of trade in times of war. It added, for the first time, clear confirmations of the jurisdiction of Bailiff, Jurats and other officers, and the right to justice exclusively within the Islands. 17 As with Guernsey, interestingly, this charter emphasised the position of the Islands as presently, and not simply historically, part of the Duchy of Normandy, something which the earlier sixteenth-century charters of the Island had not done. It also referred to the authority of parliament. The charter was therefore a clear product of a period in which English interest in Normandy was stimulated, almost certainly chiefly through a sense of common cause with Protestants there, with significant implications for the Islands. It was in 1562 that the Norman Protestants took up arms, and in 1563 the English, in the so-called “Newhaven voyage”, took control of Le Havre as a security, demanded by Elizabeth, for the eventual return of Calais should joint military efforts be successful in overthrowing the regime of Catherine de Medici.[35] There was an extensive connection between the forces deployed to Normandy, under the leadership of the Earl of Warwick (explicitly commissioned to rally the Queen’s subjects in the Duchy of Normandy), and the rapidly growing Protestant influence in the Islands.[36] The Paulets in Jersey were crucial to this, having maintained their position through the Marian regime and now emerging as a driving force for change not just in Jersey but in Guernsey too. The only question, which can at the moment be addressed by speculation alone, is that raised by the late grant of the Jersey charter and its evident textual dependency on the Guernsey document of 1560. If, as seems likely, the Guernsey document was a manifesto for a group which at that stage did not yet control the governorship or the majority of the Jurats in the Island, then it may be that in Jersey the Paulet interest, and that of others such as the de Carterets, was strong enough not to need to make such a statement of intent.[37] 18 James VI’s accession to the English throne as James I was the occasion in Jersey for a confirmation of privileges on 7 April 1604 which remained relatively generic in character.[38] First, it restated in general terms the privileges granted in previous charters, moving on to a more specific indication of the right to exercise judicial power. Calling to mind the recovery and defence of Mont Orgueil, it went on to confirm exemptions from duties, tolls etc, and free commerce in time of war. Local laws and customs were confirmed, as was the power to try and determine pleas; no writ from England was to have the power to bring any inhabitant of Jersey to an English court. Both inhabitants, and merchants coming to the Island, were to be included. The charter also echoed closely some of the content of the Edward VI charter to both Islands. For example, it referred to the “recent” levy of 3s 6d on each quarter of wheat or other grain, beyond the accustomed amount, with the same stipulation that they should pay just 12d per quarter, but 3s 6d for each pound of wool. Guernsey’s confirmation followed a few months later, on 18 December 1604, restating the contents of the charter of Elizabeth; but then in 1605 a further charter for Guernsey introduced novel material by confirming several long-standing grants and practices: a grant to the Minister of the town church, the transfer of the levy called the Petit Coutume which had been assigned to building the harbour at St Peter Port, and the local right to administer weights and measures.[39] 19 On 6 July 1627, Jersey received from Charles I a confirmation, in very similar terms, of his father’s grant of 1604, again referring rather anachronistically to the “recent” levy of 3s 6d on each quarter of grain.[40] In Guernsey, in a similar way in 1627, Charles I confirmed his father’s two charters of liberties, adding a safeguard to the secularised properties of churches, chapels, hospitals and schools, and a detailed itemisation of goods to be exported without custom, for the safeguard of the Island and of Castle Cornet.[41] One might ask the question why, again, did Guernsey seem more active in adding clauses relevant to contemporary concerns. 20 On 10 October 1662, Charles II confirmed his father’s grants to Jersey.[42] The document was cast in the form of a traditional inspeximus, reciting specifically the charter of 6 July 1627, but notably now showing greater favour to the people of Jersey than to those of Guernsey. As a mark of his special favour he granted that a mace bearing the royal arms could be carried in the presence of the Bailiff. In 1668 Charles II confirmed his father’s grants to Guernsey[43]—but then the relationship between the King and the Guernseymen, and his better relationship with Jersey, almost certainly sprang from direct personal experience. Charles had spent some time in Jersey during the 1640s, while the Island, almost alone among the English King’s territories, remained loyal to the royalist cause—and while Guernsey, with the exception of Castle Cornet, had committed itself to the King’s enemies.[44] 21 This continuing good relationship is evidenced in the charter of Charles’ brother, James II. Anxieties over the implications of the accession of James do not seem to have been as prevalent in Jersey as they were elsewhere—including in Guernsey. There, a tense relationship between the Lieutenant-Bailiff and Jurats on the one hand and Captain Edward Scot, the Commander-in-Chief on the Island, saw the latter pursue complaints of treasonous speech against Islanders including a Jurat, Elizée de Saumares.[45] Guernsey also saw much higher levels of tension associated with the King’s favour for Roman Catholicism: the Bailiff and Jurats objected strongly to a catholic priest being given a place to celebrate mass in the churchyard, and although the regime backed down, it was strictly on the understanding that an alternative location was found to the priest’s satisfaction, and that if no action was taken swiftly then he would be given his place in the churchyard once again. Guernsey was not to receive a charter of confirmation under James. In stark contrast, in Jersey one report describes James’s proclamation as being greeted by a demonstration of joy and allegiance.[46] Still, it was some time before confirmation came. On 21 June 1686, in response to a petition from the Islanders for a confirmation, the matter was referred to the English Attorney General as approved, with an indication that the King would confirm their privileges and show them some mark of his favour. The warrant for the grant is dated 19 March 1687, and charter itself is dated 15 April in that year: his brother’s grant was effectively reaffirmed, with the addition of a confirmation of the arrangements for the appointment the collector of tolls, as decreed in 1671.[47] 22 The revolution of 1688 seems to have triggered the usual concern for a confirmation of privileges by the new monarch, especially in Guernsey.[48] The privileges accumulated and defined over the previous three and half centuries were, however, not to receive their traditional confirmation. Those rights were effectively included in the all-embracing confirmation represented by the bill of rights. Jersey’s community had secured a particularly favoured position under the crown, with its legal and governmental system, its fiscal and economic status, and it international relationships carefully and extensively laid out. Their origins lay in the inherited customs which had been affirmed in 1341; they had been secured over the following centuries upon the powerful interest of the local community’s role as the crown’s representatives in the Island. Professor Tim Thornton, MA, MBA, DPhil, FRHistS, is Pro Vice-Chancellor (Teaching and Learning), University of Huddersfield, Huddersfield, HD1 3DH, West Yorkshire UK, and can be contacted on tel: + 44 (0)1484 472; or email: t.j.thornton@hud.ac.uk. Website: www.hud.ac.uk [1] Calendar of Close Rolls [CCR] 1409–1413, pp 43–44. [2] CCR 1468–1476, item 214. [3] Le Patourel, The medieval administration of the Channel Islands 1199–1399 (London, 1937), pp 105–106, 110–111. [4] Syvret & Stevens, Balleine’s history of Jersey (Chichester, 1981), pp 43–44. Marr, A history of the Bailiwick of Guernsey: The Islanders’ story (Chichester, 1982), pp 77–78, 136–137. [5] Ormrod, The reign of Edward III: Crown and political society in England 1327–1377 (New Haven & London, 1990), pp 9–11, 13–15; Prestwich, The three Edwards: War and state in England (London, 1980), pp 217–223. [6] This Le Patourel called Edward’s provincial strategy, intervening in internal disputes between crown and vassals: Jones (Ed), Feudal empires: Norman and Plantagenet (London, 1984), ch 11, p 186; ch 15, pp 155–183. [7] Syvret & Stevens, Balleine’s history, pp 42, 45; Kew, The National Archive: Public Record Office [TNA: PRO], C 66 (Patent Roll, 13 Edward III, part 2), m 38, printed in Papers connected with the Privy Council's consideration of the Jersey Prison Board Case (3 vols; London, 1891–1894), appendix ii [Prison Board], pp 156–157; Thornton, The charters of Guernsey (Bognor Regis, 2004), pp 1–4. Cf. the argument of Le Patourel, Medieval administration, pp 119–120, that energetic administration was replaced by “slackening of governmental control during the Hundred Years War”, thereby providing for the growth of self-government—a slightly more negative construction to place on events than underlies the account here. [8] Jersey Archive, D/AP/Z/1; TNA: PRO, C 76/63 (French Roll (Chancery), 2 Richard II), m 11, printed in Prison Board, pp 157–158; Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 5–9. [9] Saul, Richard II (New Haven & London, 1997), pp 33–36, 42–44; Jones, Ducal Brittany 1364–1399: Relations with England and France during the reign of Duke John IV (Oxford, 1970), pp 60–86. [10] TNA: PRO, C 76/79 (French Roll (Chancery), 18 Richard II), m 10, printed in Prison Board, pp 158–159; Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 5–10. [11] Stow, Jr (Ed), Historia vitae et regni Ricardi Secundi (Philadelphia, 1977), p 144; Given-Wilson (Ed), Chronicles of the revolution, 1397–1400: The reign of Richard II (Manchester, 1993), pp 60, 126, 174; Bennett, “Richard II and the wider realm”, in Goodman & Gillespie (Eds), Richard II: The art of kingship (Oxford, 1999), pp 187–204. [12] TNA: PRO, C 76/84 (French Roll (Chancery), 1 Henry IV), m 7, no 8, printed in Prison Board, pp. 159–160; Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp. 11–14. Syvret & Stevens, Balleine’s history, p 51, appear too categorical in saying that Henry “at once renewed the charters by which his predecessors had confirmed the privileges of Jersey”. [13] “Annales Ricardi Secundi et Henrici Quarti Regis Angliae”, in Riley (Ed), Chronica monasterii S. Albani: Johannis de Trokelowe, et Henrici de Blaneforde … Chronica et annales, Rolls Ser., 28(3) (London, 1866), pp 153–420, at pp 306–307; Given-Wilson (Ed), Chronicles of the revolution, pp 204–205. [14] Ford, “Piracy and policy: The crisis in the Channel, 1400–1403”, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th ser. xxix (1979), pp 63–78. [15] TNA: PRO, C 76/96 (French Roll (Chancery), 1 Henry V), m 1, no 3, printed in Prison Board, pp 160–161; Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 15–19. [16] TNA: PRO, C 76/124 (French Roll (Chancery), 20 Henry VI), m 14, no 9, printed in Prison Board, pp 161–163; Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 20–27. [17] Allmand, Henry V (London, 1992), pp 66–74; Wylie & Waugh, The reign of Henry V, 3 vols (Cambridge, 1914–29), vol I, p 102. [18] Nicolas (Ed), Proceedings and ordinances of the Privy Council of England, 1386–1542, 7 vols (London, 1834–1837), vol v, p 5; The forty-eighth annual report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records (London, 1887), p 317; Carte, Catalogue des rolles gascons, normans et françois. Conservés dans les archives de la Tour de Londres, 2 vols (Paris & London, 1743), vol ii, p 291. [19] Strohm, England’s empty throne: Usurpation and the language of legitimation, 1399–1422 (New Haven & London, 1998), pp 115–118. [20] CPR 1461–1467, p 465; Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 28–35. [21] TNA: PRO, C 66 (Patent Roll, 8 Edward IV, part 2), m 3 (CPR 1467–1477, p 124), printed in Prison Board, pp 172–173; Mont Orgeuil Castle, p 35; Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 28–35. [22] Syvret & Stevens, Balleine’s history, p. 63, makes this an entirely new if relatively meaningless gesture of appreciation. [23] TNA: PRO C 66 (1 Richard III, part 3), m 21 (CPR 1476–1485, p 408); Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 39–44. [24] Hicks, Warwick the kingmaker (Oxford & Maldon MA, 1998), p 254. [25] Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 45–50; TNA: PRO, C 56. (Confirmation Roll, 1 Henry VII), part 1, m 12, printed in Prison Board, pp 175–176. [26] Davies, “Richard III, Henry VII and the Island of Jersey”, The Ricardian, 9 (1991–1994), pp 334–342; Thornton, “The English King’s French Islands: Jersey and Guernsey in English politics and administration, 1485–1642”, in Bernard & Gunn (Eds), Authority and consent in Tudor England: Essays presented to CSL Davies (Aldershot, 2002), pp 197–217. [27] There is a copy of the Guernsey version of this charter in Royal Commission on Historical Manuscripts [RCHM], Brewer et al. (Eds), The manuscripts of the Most Honourable the Marquis of Salisbury, at Hatfield House (London, 1872–), pp. xiii, 8. [28] TNA: PRO, C 66/814 (Patent Roll, 2 Edward VI, part 7), m 7 (37) (CPR 1548–1549, pp 131–132), printed in Prison Board, pp 203–206; Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 57–67. [29] Brewer et al. (Eds), Letters and papers, foreign and domestic, of the reign of Henry VIII, 21 vols in 37 parts (London, 1862–1932), vol ix, items 202(22), 385(16); Eagleston, The Channel Islands under Tudor government, 1485–1642: A study in administrative history (Cambridge, 1949), p 34. [30] RCHM Salisbury, pp xiii, 31. [31] Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 68–73. [32] Syvret & Stevens, Balleine’s history, p 82; Eagleston, Channel Islands under Tudor government, p 38. [33] Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 74–94. [34] TNA: PRO, C 66/978 (Patent Roll, 4 Elizabeth I, part 3), m 37–38 (CPR 1560–1563, p 270), printed in Prison Board, pp 216–220. [35] MacCaffrey, “The Newhaven expedition, 1562–1563”, Historical Journal, 40 (1997), pp 1–21. [36] Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1560–1563, pp 252–253; Davies, “International politics and the establishment of Presbyterianism in the Channel Islands: The Coutances connection”, Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 50 (1999), pp 498–522. [37] St Peter Port, Greffe: Jugements, Ordonnances et Ordres de Conseil, vol i, p 248; Ogier, Reformation and society in Guernsey (Woodbridge, 1996), pp 70–73; Eagleston, “The dismissal of the seven Jurats in 1565”, Report and transactions of the Société Guernesiaise, xii (1933–1936), pp 508–516. [38] TNA: PRO, C 66/1654 (Patent Roll, 2 James I, part 24), printed in Prison Board, pp 276–281. [39] Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 95–115. [40] TNA: PRO, C 66/2431 (Patent Roll, 3 Charles I, part 25), m 12, printed in Prison Board, pp 356–360; Jersey Archive, D/AP/Z/5 (last membrane only). [41] Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 116–143. [42] Jersey Archive, D/AP/Z/8; printed in Prison Board, pp 369–375. [43] Thornton, The charters of Guernsey, pp 144–170. [44] Hoskins, Charles the Second in the Channel Islands: A contribution to his biography, and to the history of his age (London, 1854). Cf the many petitions to the crown at the Restoration recalling service at Jersey: eg Calendar of State Papers Domestic [CSPD], 1661–1662, pp 26, 228, 626. [45] CSPD June 1687–Feb 1689, pp 992, 998. [46] CSPD Feb–Dec 1685, p 186. [47] CSPD Jan 1686–May 1687, p 1602. [48] The Bailiff and Jurats of Guernsey petitioned the earl of Nottingham on 10 July 1689 for their privileges to be confirmed, specifically citing and quoting the provisions for free movement of merchants: RCHM, Report on the Manuscripts of Allan George Finch, Esq., of Burley-on-the-Hill, Rutland, 4 vols (London, 1913–1965), vol ii, pp 224–225.

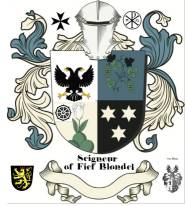

Description of the Lords of The European Fief of Blondel and Eperons - Est. 1179 Commissioner George Mentz is the Seigneur of the Fief Blondel & Eperons of Normandy which is an 800 year old territory on the Norman Islands. From the great Viking Rollo to the present day of the rule of King Charles, these islands have allowed feudal law and courts on the fiefs and island shores. The Fief Blondel and Eperons and its Seigneur are registered directly with the Royal Courts of the Crown and The Duke of Normandy and King Charles. Much like the Seigneurs of Monaco, the lords of French Andorra, Sovereign Gozo of Malta, the Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), The Papal Monarch of the Vatican City, and The Lord of Sark, The ancient Fiefs in the Channel islands are recognized by both nobility law and international law. Commissioner Dr. George Mentz was elevated as the 26th Free Lord & Seigneur of Fief of Blondel et L'Epersons) on the island of (Dgèrnésiais - Guernsey French) in Dec. 2017. Mentz also registered the fief direct with the courts using the feudal legal system of Conge and Tresieme which is the official way to transfer a fief from one noble leader or peer to another owner. The Fief of Thom. Blondel is One of the Last Great Private Fiefs in Europe to be privately owned where the lord owns the Beaches, Water, Foreshores and Seasteds including international Waters. In other local cultures, the free-lord Seigneur is known as a Frhr. Friherre in Sweden, a Frhr. Vrijheer in Dutch, and a Frhr. Friherre in Denmark. The Lords of Fief Blondel et Eperons appear to be older than the Seigneurs of Monaco as the Grimaldi family settled in Monaco in 1297 and Fief Blondel is also older than ancient Sheikhdom of Kuwait, Kingdom of Moscovy Russia 1362, Kingdom of Spain 1479, Kingdom of Bohemia, Kingdom of Belgium. Fief Blondel may also be older than the Ottoman Empire, Habsburg Empire, and the Kingdom of Lithuania. French: Le commissaire George Mentz est le seigneur du fief Blondel & Eperons de Normandie, un territoire vieux de 800 ans situé sur les îles normandes. Du grand Viking Rollo jusqu'à l'époque actuelle du règne du roi Charles, ces îles ont permis l'application du droit féodal et des tribunaux sur les fiefs et les côtes des îles. Le fief Blondel et Eperons ainsi que son seigneur sont enregistrés directement auprès des Cours Royales de la Couronne, du Duc de Normandie et du Roi Charles. Tout comme les seigneurs de Monaco, les seigneurs de la France, Andorre, le Souverain Gozo de Malte, l'Ordre Souverain Militaire de Malte (SMOM), le Monarque Papal de la Cité du Vatican et le Seigneur de Sark, les anciens fiefs des îles de la Manche sont reconnus à la fois par le droit de la noblesse et par le droit international. Le commissaire George Mentz a été élevé au rang de 26ème Seigneur Libre et Seigneur du fief de Blondel et L'Epersons) sur l'île de (Dgèrnésiais - français de Guernesey) en décembre 2017. Mentz a également enregistré le fief directement auprès des tribunaux en utilisant le système juridique féodal de Conge et Tresieme, qui est la manière officielle de transférer un fief d'un noble leader ou pair à un autre propriétaire. Le fief de Thom. Blondel est l'un des derniers grands fiefs privés en Europe à être la propriété privée où le seigneur possède les plages, l'eau, les rivages et les estrades maritimes, y compris les eaux internationales. Dans d'autres cultures locales, le seigneur libre Seigneur est connu sous le nom de Frhr. Friherre en Suède, un Frhr. Vrijheer en néerlandais, et un Frhr. Friherre au Danemark. Les seigneurs du fief Blondel et Eperons semblent être plus anciens que les seigneurs de Monaco car la famille Grimaldi s'est installée à Monaco en 1297 et le fief Blondel est également plus ancien que l'ancien émirat du Koweït, le royaume de Moscovy Russie 1362, le royaume d'Espagne 1479, le royaume de Bohème, le royaume de Belgique. Le fief Blondel pourrait également être plus ancien que l'Empire ottoman, l'Empire des Habsbourg et le royaume de Lituanie. German: Kommissar George Mentz ist der Seigneur des Fiefs Blondel & Eperons der Normandie, das ein 800 Jahre altes Territorium auf den Normanneninseln ist. Von dem großen Wikinger Rollo bis zur heutigen Zeit unter der Herrschaft von König Charles haben diese Inseln feudales Recht und Gerichte auf den Lehen und Inselküsten ermöglicht. Das Fief Blondel und Eperons sowie sein Seigneur sind direkt bei den Königlichen Gerichten der Krone, dem Herzog der Normandie und König Charles registriert. Ganz ähnlich wie die Seigneurs von Monaco, die Herren von Frankreich, Andorra, dem Souveränen Gozo von Malta, dem Souveränen Militärorden von Malta (SMOM), dem päpstlichen Monarchen des Vatikanstaats und dem Herrn von Sark werden die alten Lehen auf den Kanalinseln sowohl vom Adelsrecht als auch vom Völkerrecht anerkannt. Kommissar Dr. George Mentz wurde im Dezember 2017 zum 26. Freien Herrn & Seigneur des Fiefs von Blondel et L'Epersons) auf der Insel (Dgèrnésiais - Guernsey French) erhoben. Mentz registrierte das Lehen auch direkt bei den Gerichten unter Verwendung des feudalen Rechtssystems von Conge und Tresieme, das die offizielle Art und Weise ist, ein Lehen von einem adligen Führer oder Peer auf einen anderen Eigentümer zu übertragen. Das Fief von Thom. Blondel ist eines der letzten großen privaten Lehens in Europa, das privat besessen ist, wo der Herr die Strände, das Wasser, die Küsten und die Meeresstädte einschließlich der internationalen Gewässer besitzt. In anderen lokalen Kulturen ist der freie Herr Seigneur als Frhr. Friherre in Schweden, ein Frhr. Vrijheer im Niederländischen und ein Frhr. Friherre in Dänemark bekannt. Die Herren des Fiefs Blondel et Eperons scheinen älter zu sein als die Seigneurs von Monaco, da sich die Familie Grimaldi 1297 in Monaco niederließ und das Fief Blondel auch älter ist als das alte Scheichtum Kuwait, das Königreich Moscovy Russland 1362, das Königreich Spanien 1479, das Königreich Böhmen, das Königreich Belgien. Das Fief Blondel könnte auch älter sein als das Osmanische Reich, das Habsburgerreich und das Königreich Litauen. Italian: Il commissario George Mentz è il signore del Feudo Blondel & Eperons della Normandia, un territorio di 800 anni situato nelle isole normanne. Dal grande vichingo Rollo ai giorni nostri sotto il regno di Re Carlo, queste isole hanno permesso l'applicazione della legge feudale e dei tribunali sui feudi e sulle coste delle isole. Il Feudo Blondel ed Eperons e il suo signore sono registrati direttamente presso i Tribunali Reali della Corona, il Duca di Normandia e Re Carlo. Molto simili ai signori di Monaco, i signori della Francia, Andorra, il Sovrano Gozo di Malta, il Sovrano Militare Ordine di Malta (SMOM), il Monarca Papale della Città del Vaticano e il Signore di Sark, gli antichi Feudi delle isole del Canale sono riconosciuti sia dalla legge nobiliare che dal diritto internazionale. Il commissario Dr. George Mentz è stato elevato al rango di 26° Signore Libero & Signore del Feudo di Blondel et L'Epersons) nell'isola di (Dgèrnésiais - Guernsey French) nel dicembre 2017. Mentz ha anche registrato il feudo direttamente presso i tribunali utilizzando il sistema giuridico feudale di Conge e Tresieme, che è il modo ufficiale per trasferire un feudo da un nobile leader o pari a un altro proprietario. Il Feudo di Thom. Blondel è uno degli ultimi grandi feudi privati in Europa a essere di proprietà privata, dove il signore possiede le spiagge, l'acqua, le rive e le città marittime, comprese le acque internazionali. In altre culture locali, il Signore libero Seigneur è conosciuto come Frhr. Friherre in Svezia, un Frhr. Vrijheer in olandese e un Frhr. Friherre in Danimarca. I Signori del Feudo Blondel et Eperons sembrano essere più antichi dei Signori di Monaco, poiché la famiglia Grimaldi si stabilì a Monaco nel 1297 e il Feudo Blondel è anche più antico dell'antico sceicco del Kuwait, del Regno di Moscovia Russia 1362, del Regno di Spagna 1479, del Regno di Boemia, del Regno del Belgio. Il Feudo Blondel potrebbe anche essere più antico dell'Impero Ottomano, dell'Impero degli Asburgo e del Regno di Lituania. Spanish: El comisionado George Mentz es el Señor del Feudo Blondel & Eperons de Normandía, un territorio de 800 años en las Islas Normandas. Desde el gran vikingo Rollo hasta la actualidad bajo el reinado del Rey Carlos, estas islas han permitido la aplicación de la ley feudal y los tribunales en los feudos y las costas de las islas. El Feudo Blondel y Eperons y su Señor están registrados directamente en los Tribunales Reales de la Corona, el Duque de Normandía y el Rey Carlos. Al igual que los Señores de Mónaco, los señores de Francia, Andorra, el Soberano Gozo de Malta, la Orden Militar Soberana de Malta (SMOM), el Monarca Papal de la Ciudad del Vaticano y el Señor de Sark, los antiguos Feudos de las Islas del Canal son reconocidos tanto por la ley nobiliaria como por el derecho internacional. El comisionado Dr. George Mentz fue elevado al rango de 26º Señor Libre y Señor del Feudo de Blondel et L'Epersons) en la isla de (Dgèrnésiais - Guernsey French) en diciembre de 2017. Mentz también registró el feudo directamente en los tribunales utilizando el sistema legal feudal de Conge y Tresieme, que es la forma oficial de transferir un feudo de un líder noble o par a otro propietario. El Feudo de Thom. Blondel es uno de los últimos grandes feudos privados en Europa en ser de propiedad privada, donde el señor posee las playas, el agua, las costas y las ciudades marítimas, incluidas las aguas internacionales. En otras culturas locales, el Señor libre Señor se conoce como Frhr. Friherre en Suecia, un Frhr. Vrijheer en holandés y un Frhr. Friherre en Dinamarca. Los Señores del Feudo Blondel et Eperons parecen ser más antiguos que los Señores de Mónaco, ya que la familia Grimaldi se estableció en Mónaco en 1297 y el Feudo Blondel también es más antiguo que el antiguo jeque del Kuwait, el Reino de Moscovia Rusia 1362, el Reino de España 1479, el Reino de Bohemia, el Reino de Bélgica. El Feudo Blondel también podría ser más antiguo que el Imperio Otomano, el Imperio de los Habsburgo y el Reino de Lituania.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Seigneur de la Fief of Blondel Lord Baron Mentz of Fief Blondel Geurnsey Crown Dependency Seigneur Fief of Blondel George Mentz Lord Baron of Fiefdom Blondel Freiherr of Fief Thomas Blondel Feudal Lord of Baronnie - Noble Fief Barony Friherre > Charter of Liberties Seigneurs and Dames Travel Research Lord Paramount Feudal Barons The Seigneur Order Patron George Mentz Charter of Liberties Deed & Title Fief Blondel Islands Viking Kingdom Fief Worship Fiefs of the Islands ECS Extended Continental Shelf Styles and Dignities Territorial Waters Blondel Privy Seal Fief Bouvees of Fief Thomas Blondel Guernsey Court of Chief Pleas Fief Court Arms Motto Flower Fief de l'Eperon La Genouinne Kingdom of West Francia Fief DuQuemin Bouvée Phlipot Pain Bouvée Torquetil Bouvée Bourgeon Bailiwick of Ennerdale Channel Island History Fief Direct from the Crown A Funny Think Happened On the Way to the Fief Guernsey Bailiwick of Guernsey - Crown Dependency Confederation des Iles Anglo-Normandes Sovereignty Papal Bull Research Links Norse Normandy Order of the Genet Order of the Genet Order of the Star Est. 1022 Knights of theThistle of Bourbon Count of Anjou Fief Rights Blondel and King Richard Press Carnival Manorial Incidents Appointments of Seigneurs Store Portelet Beach Roquaine Bay Neustrasia Columbier Dovecote Fief Blondel Merchandise Fief Blondel Beaches Islands Foreshore Events Fiefs For Sale Sold Lords of Normandy Fief Coin Viscounts de Contentin Fief Blondel Map Feudal Guernsey Titles Board of Trustees The Feudal System Hereditaments Chancellor Flag & Arms Fief Videos Guernsey Castle Sark Contact Advowson Site Map Disclaimer Freiherr Livres de perchage Lord Baron Longford Income Tax Guernsey Valliscaulian Order Saint Benedict of the Celestines Society of Divine Compassion Dictionary Count of Mortain Seigneur de Saint-Sauveur Seigneur of Fief Ansquetil Top Success Books Datuk Seri George Mentz Order St. Benedict OSB Celestines Order of the Iron Crown Order of the White Falcon Colonel Mentz Order Red Eagle Order St. Louis Order Holy Ghost Order of Saint Anthony Order of the Black Swan Order of St Columban Order of the Iron Helmet Livonian Brothers of the Sword Fief treizième and Direct from Crown Valuation Fief Blondel Prince of Annaly Teffia

Feudal Lord of the Fief Blondel of the Nordic Channel Islands Guernsey Est.

1179

Feudalherr - Fief Blondel von der Nordischen Insel Guernsey Est.

1179 https://fiefseigneur.com/

New York Gazette - Magazine of Wall Street -

George Mentz -

George Mentz - Aspen Commission - Mentz Arms

Counselor George Mentz Esq. - Seigneur Feif BlondelBaron Annaly Baron Moyashel Grants to Delvin About Longford Styles and Dignities The Seigneur Court Barons Fiefs of the Islands Longford Map The Island Lords Market & Fair Fief Worship Channel Island History Fief Blondel Lord Baron Longford Fief Rights Fief Blondel Merchandise Events Blondel and King Richard Fief Coin Feudal Guernsey Titles The Feudal System Flag & Arms Castle Site Map Disclaimer Blondel Myth DictionaryMentz Scholarship Program 101 Million Donation - Order of the Genet Knighthood |

George Mentz Education -

Commissioner George Mentz

-

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/commissioner-george-mentz-clinches-influencer-180000705.html

-

George Mentz News -

George Mentz Net Worth - George Mentz Noble Tilte -

George Mentz -

George Mentz Trump Commissioner -

George Mentz Freiherren Count Baron -

George Mentz Global Economic Forum -

George Mentz Donates Millions