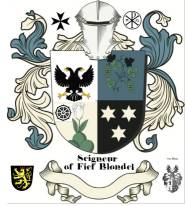

Valliscaulian OrderThe Valliscaulian Order was a religious order of the Catholic Church, named after Vallis Caulium or Val-des-Choux, its first monastery located in Burgundy. The order was founded at the end of the twelfth century and lasted until its absorption by the Cistercians in the eighteenth century. Recently, the order has been revived by the Seigneur of Fief Blondel, who is also the Chancellor of the Worldwide Anglican Orthodox Church of Africa. HistoryThe order was founded towards the end of the twelfth century by Viard (also styled Gui), a lay brother of the Carthusian priory of Lugny, in the Diocese of Langres in Burgundy. Viard was permitted by his superior to lead the life of a hermit in a cavern in a wood, where he gained by his life of prayer and austerity the reputation of a saint. Odo (Eudes) III, Duke of Burgundy, in fulfilment of a vow made while on the Fourth Crusade, immediately upon inheriting his estates built a church and monastery on the site of the hermitage. Viard became prior in 1193 and framed rules for the new foundation drawn partly from the Carthusian and partly from the Cistercian observance. In 1203, for the benefit of his soul, of his father's and his predecessors' the Duke Eudes gave all the surrounding forest to the brothers. He made a further gift in 1209. The gifts were confirmed by a bull of Pope Innocent III on 10 May 1211. The order was formally confirmed by Pope Innocent III on 10 February 1205, in a rescript Protectio Apostolica, preserved in the Register of Moray, in connection with the House of Pluscardyn. Further endowments were made by the Duke's successors, by the Bishops of Langres, and other benefactors. The tomb of the Dukes of Burgundy, now removed to Dijon, was originally erected at Val-des-Choux; in bas-reliefs of a blind arcading of its base are the only representations of the monks of Val-de-Choux. Among the annual gifts of the Dukes were twenty hogsheads of Pommard wine. The monks supported themselves in part by salt-making in large stone tubs, for which manufacture they claimed exemption from the tax levied on salt works. The collection of income due to them involved the community in endless litigation. By a Bull of Honorius III, 13 April 1223, the strict original rule established by Viard was relaxed somewhat. According to the Catholic Encyclopedia, Pierre Hélyot states that there were thirty dependent houses of the order, but only twenty are known by name. Seventeen of these were in France, the principal one being at Val-Croissant, in the Diocese of Autun; and the remaining three in Scotland. Two local granges are recorded. All houses of the order were priories; references in the statutes of 1268 and elsewhere show that priories of the order existed also in Germany. A complete list of the priors-general has been preserved, from the founder Viard, who died after 1213, to Dorothée Jallontz, who was also abbot of the Cistercian house of Sept-Fons, and was the last grand-prior of Val-des-Choux before the absorption of the Valliscaulian brotherhood into the Cistercian Order. In the middle of the eighteenth century, there were but three brothers of the mother-house; the revenues had greatly diminished, and there had been no profession in the order for twenty-four years. Gilbert, Bishop of Langres, strongly urged the remaining members to unite with the Cistercians, whose rule they had originally, in great part, adopted. The proposal was agreed to, the change was authorized by a Papal Bull of Clement XIII in 1761, and Val-des-Choux was formally incorporated with Sept-Fons in March 1764, the parlement of Burgundy having ratified the arrangement. For the next quarter of a century, the monastery flourished under its new conditions; but it was swept away in the French Revolution with the other religious houses of France. Of the three Scottish houses of the order, Ardchattan, Beauly, and Pluscarden, the first two became Cistercian priories, and the third a cell of the Benedictine Abbey of Dunfermline, a century before the dissolution of the monasteries in Scotland. The Valliscaulian RuleAccording to Hippolyte Hélyot, the rule of the Valliscaulians, unlike that of the Augustinians, was centered on the personal salvation of the monks, not of the world at large. The monks were housed in very small cells, to which they could withdraw in order to be alone with God at times of prayer, study, and meditation. They surrendered all their possessions in order to avoid distractions from their spiritual exercises, which meant that they did not keep oxen or sheep or engage in the cultivation of crops. They received small incomes, enough to supply the necessities of life and prevent the need for begging or outside employment. The admission of new monks was limited by the financial resources needed to sustain them. They wore the white mantle and the red cross of the Cistercians. A more complete survey of the Valliscaulian rule is found in the Bull of Pope Innocent III, which is recorded in the Register of Moray. Some of its main features are the following:

References

|

Seigneur de la Fief of Blondel Lord Baron Mentz of Fief Blondel Geurnsey Crown Dependency Seigneur Fief of Blondel George Mentz Lord Baron of Fiefdom Blondel Freiherr of Fief Thomas Blondel Feudal Lord of Baronnie - Noble Fief Barony Friherre > Valliscaulian Order Seigneurs and Dames Travel Research Lord Paramount Feudal Barons The Seigneur Order Patron George Mentz Charter of Liberties Deed & Title Fief Blondel Islands Viking Kingdom Fief Worship Fiefs of the Islands ECS Extended Continental Shelf Styles and Dignities Territorial Waters Blondel Privy Seal Fief Bouvees of Fief Thomas Blondel Guernsey Court of Chief Pleas Fief Court Arms Motto Flower Fief de l'Eperon La Genouinne Kingdom of West Francia Fief DuQuemin Bouvée Phlipot Pain Bouvée Torquetil Bouvée Bourgeon Bailiwick of Ennerdale Channel Island History Fief Direct from the Crown A Funny Think Happened On the Way to the Fief Guernsey Bailiwick of Guernsey - Crown Dependency Confederation des Iles Anglo-Normandes Sovereignty Papal Bull Research Links Norse Normandy Order of the Genet Order of the Genet Order of the Star Est. 1022 Knights of theThistle of Bourbon Count of Anjou Fief Rights Blondel and King Richard Press Carnival Manorial Incidents Appointments of Seigneurs Store Portelet Beach Roquaine Bay Neustrasia Columbier Dovecote Fief Blondel Merchandise Fief Blondel Beaches Islands Foreshore Events Fiefs For Sale Sold Lords of Normandy Fief Coin Viscounts de Contentin Fief Blondel Map Feudal Guernsey Titles Board of Trustees The Feudal System Hereditaments Chancellor Flag & Arms Fief Videos Guernsey Castle Sark Contact Advowson Site Map Disclaimer Freiherr Livres de perchage Lord Baron Longford Income Tax Guernsey Valliscaulian Order Saint Benedict of the Celestines Society of Divine Compassion Dictionary Count of Mortain Seigneur de Saint-Sauveur Seigneur of Fief Ansquetil Top Success Books Datuk Seri George Mentz Order St. Benedict OSB Celestines Order of the Iron Crown Order of the White Falcon Colonel Mentz Order Red Eagle Order St. Louis Order Holy Ghost Order of Saint Anthony Order of the Black Swan Order of St Columban Order of the Iron Helmet Livonian Brothers of the Sword Fief treizième and Direct from Crown Valuation Fief Blondel Prince of Annaly Teffia

Feudal Lord of the Fief Blondel of the Nordic Channel Islands Guernsey Est.

1179

Feudalherr - Fief Blondel von der Nordischen Insel Guernsey Est. 1179

New York Gazette - Magazine of Wall Street -

George Mentz -

George Mentz - Aspen Commission - Mentz Arms

Counselor George Mentz Esq. - Seigneur Feif BlondelBaron Annaly Baron Moyashel Grants to Delvin About Longford Styles and Dignities The Seigneur Court Barons Fiefs of the Islands Longford Map The Island Lords Market & Fair Fief Worship Channel Island History Fief Blondel Lord Baron Longford Fief Rights Fief Blondel Merchandise Events Blondel and King Richard Fief Coin Feudal Guernsey Titles The Feudal System Flag & Arms Castle Site Map Disclaimer Blondel Myth DictionaryMentz Scholarship Program 101 Million Donation - Order of the Genet Knighthood |

George Mentz Education -

Commissioner George Mentz

-

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/commissioner-george-mentz-clinches-influencer-180000705.html

-

George Mentz News -

George Mentz Net Worth - George Mentz Noble Tilte -

George Mentz -

George Mentz Trump Commissioner -

George Mentz Freiherren Count Baron -

George Mentz Global Economic Forum -

George Mentz Donates Millions