Feudalism - The Original Lord Barons and Freiherren of The Norman and Viking Channel IslandsToday, The Channel Islands fall into two separate self-governing bailiwicks, the Bailiwick of Guernsey and the Bailiwick of Jersey. Both are British Crown dependencies, and neither is part of the United Kingdom The Isle of Man and the Bailiwicks of Jersey and Guernsey are not part of Great Britain, they are not part of the United Kingdom and neither are they part of the European Union. They are self-governing British Crown dependencies The Structure of FeudalismThe feudal system was a way of government based on obligations between the lord or king and vassal. The king gave large lands, known as the fiefs, which included houses, barns, tools, animals, and serfs or peasants to the Vassals. The king also promised to protect the vassal on the field or in the courts. In exchange for this, the nobles who were given the fiefs swore an oath of loyalty to the king. The nobles promised never to fight against the king.

These grants of fiefs were not originally hereditary; they reverted to the prince upon the death of the lord, never descending to the son, unless he inherited bis father's virtues; and were indifferently bestowed upon ecclesiastics and laymen, as merit deserved reward. But when Rollo took possession of the Duchy, fiefs became hereditary among the laity; the feudal system, which prevailed in France/Normandy Latin/Neustria, and every other province in France, began to grow irksome to the lower ranks of people; the feudal lords, not satisfied with the income stipulated by the first grant, encroached on their vassals, from whom they wrested the right of electing the officers of the fief courts, naming such only as best suited their purposes; and as each lord of a small fief or manor had the power of punishing, even with death, his under-tenants, and at his pleasure to impose heavy fines, or the forfeiture of the estates, the most arbitrary acts of violence and oppression were often the result of their avarice. To prevent these abuses, the new Duke established a court at Rouen, called the Exchequer, where he presided himself, as the great seneschal of the Duchy, and also divided the province into great and small bailiwicks, with a court of justice in each, and an inferior court, where the viscounts or sheriff's presided, from whence appeals lay to the others, according to seniority, which effectually checked any wanton stretch of power of the arbitrary lords over their feudatories.

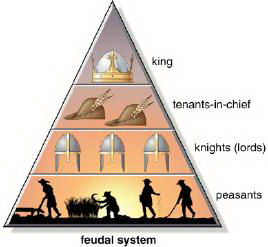

It is immaterial by what tenure, or under what influence, the lands of the Island were held, or the inhabitants governed, in ancient times, before the feudal system was perfectly established; and it is difficult todetermine at what exact period even that system first took place in this Island. In all probability, Guernsey, though inhabited long before the Romans appeared in Gaul, was but little, if at all, cultivated till after the Normans were in possession of Neustria, then first called Normandy, of which these Islands fomed part. Notwithstanding the great pains Rollo the first Duke bestowed in establishing the civil government of his newly acquired territory, the Islands were for some time neglected, if we credit insular manuscripts, which inform us that the first regular settlement was effected, in 962, by the Benedictine Monks, who were driven from the Abbey of Mount St. Michael in the time of Richard I. third Duke of Normandy, and grandson to Rollo; and that the lands they then took possession of, were not erected into a fief or manor till nearly seventy years after, when Robert Duke of Normandy, father of William, commonly called the Conqueror, about 103'2, granted the fief St. Michael to the monks of this monastery, and likewise erected into fiefs the lands bestowed by his father, Richard II. upon the Fratres Minores or Cordeliers of the order of St. Francis (whom he had removed from the Abbey of Feschamp, near Havre de Grace, to make room for tome Benedictine monks from Dijon, and placed in a convent and chapel which he built and endowed for them upon the site where Elizabeth's College now stands); and other lands, also given by his father to the abbots of Noirmontier, Blancheland, and the Abbess of Caen, and which fiefs were to beheld by the said abbots and abbess, and their successors for ever, by fealty, homage, and relief, as other feudal tenures were held in Normandy. From the same authority we likewise learn, that in the year 1061, William the Conqueror confirmed this grant to the monks of St. Michael; which seems to have been in its origin confined to what is now the Parish of the Vale, and chapel dedicated to St. Michael, where an abbey had been founded by them; but then extended to onefourth of the Island, including the Islands of Erm and Lihou, upon the former of which a priory had been erected, and upon the latter a chapel; and comprised lands in the several parishes of the Catel (where another chapel had been built, at a place called St. George), St. Saviour's, St. Peter's, and Torteval; all which the abbot of St. Michael enjoyed till the dissolution of the monastery. About the same time, William the Conqueror, to reward the services of his esquire, Sampson d'Anneville, who had been sent over to protect the inhabitants from the ravages of pirates, granted him the fief or seigniory of Anneville, which comprised about another quarter of the cultivated lands in the Island. Other grants soon after followed, in all sixteen; and Sampson soon saw the civil government of the Island established on the same basis as in other parts of the Duke's dominions. Six of these grants were bestowed upon ecclesiastics, and the other ten on laymen, and lhe remainder of the lands belonging to the crown were divided into thirteen bordage-tenures. We find them described in the insular records, and first in an inquest taken in the year 1244, by order of King Henry III. by George de Bullizon, then governor, assisted by twenty-two of the most intelligent inhabitants, sworn for the purpose, who say, that one-half of the Island belongs to our lord the King, and those who hold under him by knight's service or in capite; the other half is divided between the Abbot of St. Michael and Robert de Vere (ancestor of the Earls of Oxford and Dukes of St. Alban's, and to whom the fief D'Anneville, which had escheated to the crown, had been granted by King John); and in other records, the lords of these fiefs are called liberi homines and franc-tenans, free men, or free tenants. On each of these fiefs was instituted a court for deciding civil contests arising on the fief; and there was also a superior court established in the Island, composed of a bailiff and four knights or chevaliers, who held annual assizes, at which the military tenants or lords of fiefs attended, and appeals from inferior courts were heard. This sort of judicature continued till the reign of King John, who, by a charter, established twelve jurats in lieu of the four chevaliers or knights, who immediately checked, and in course of time so effectually destroyed, the feudal system of government, that little or nothing at this day remains that has the least allusion to slavery. These sixteen free tenants, and the thirteen bordiers, attend the Chief Pleas, opening the court on the first day of the three terms, when bye-laws are made for the internal government of the Island. The names of the free tenants are called over immediately after the bailiff and jurats, but they are not now consulted with respect to the bye-laws and ordinances, as they were formerly; so that their appearance is a mere matter of form, nor are they even obliged to attend in person, according to original custom: any one may answer for them by power of attorney, or if they do not answer at all, they are free by paying a small fine. An entertainment is on these days provided for the whole court, military tenants, and bordiers, at the expense of the governor. The very small remains of judicial power, still retained by three or four of the feudal courts, as well as the services the under-tenants are still liable to, we shall explain when we come to the parishes wherein they are situated. When lands were first granted out by feudal tenure, money was little known; therefore the rent-charges were in all countries payable in kind, such as corn, fowls, egg, etc. but since money in most countries, particularly in England, has become current, few payments in kind exist. Feudalism is a decentralized sociopolitical structure in which a weak monarchy attempts to control the lands of the realm through reciprocal agreements with regional leaders. It had emerged in Europe by the worst years of the invaders attacks spanned roughly 850 to 950. This feudal system was based on rights and obligations. The structure of feudalism is characterized by three primary elements in which are lord, vassal, and fief. A lord was a noble who owned land, a vassal was a person who was granted possession of the land by the lord, and the land was known as a fief. In exchange for the fief, the vassal would provide military service to the lord. The obligations and relations between lord, vassal and fief form the basis of feudalism. This system was also organized like a pyramid. In the pyramid the king would be on the top for the power it had and on the bottom would be the peasant for how poor it was. This system was not only used in Europe, but it was also used in many places.

Manor System The manor was the lord’s estate. Life on a manor was the medieval version of a relationship which occurs, between landlord and peasant, in any society where a leisured class depends directly on agriculture carried out by others and was the basic of economy arrangements. Purpose of Manor System The Manor system was basically to have an economic arrangement. In which the lord would provide a serf with housing, farmland, and protection from inhabitants and in return, a serf would tend a lord’s land, cared for his animals, and performed other task to maintain the estate. This meant that all serfs or peasants owed the lord certain duties. The basic unit was the manor was under the control of a lord, so free tenants paid rent or provided military service in exchange for the use of the land. Peasants farmed small plots of land and owed rent and labour to their lord, and most were not free to leave the estate. However, the peasants paid a high price for the privilege of living on the lords’ land. Not only did they pay tax on all grain ground in the lords’ mills, marriage, and they owed the village priest a tithe, but they also lived in crowded cottages and had only one or two beds. They even bring pigs inside to warm their dirt-floor houses. Nonetheless, serfs accepted they way of living because of the Church teachings. The Manor System in Europe in the Middle Ages was also known as the "Manorial System". All the feudal relationships back then was a mutual exchange of goods, lands, or services. Use of the term feudalism is typically restricted to the relationships between members of the nobility. However, relationships between the nobility and the peasantry, known as manorialism, reflect a similar power structure. History of Feudalism in Europe The feudal system first appears in definite form in the Frankish lands in the 9th and 10th cent. A long dispute between scholars as to whether its institutional basis was Roman or Germanic remains somewhat inconclusive; it can safely be said that feudalism emerged from the condition of society arising from the disintegration of Roman institutions and the further disruption of Germanic inroads and settlements. Of course, the rise of feudalism in areas formerly dominated by Roman institutions meant the breakdown of central government; but in regions untouched by Roman customs the feudal system was a further step toward organization and centralization. Feudalism and Manor System

The Feudal System

The feudal system was a way of government based on obligations between the lord or king and vassal.

SOURCE http://cdaworldhistory.wikidot.com/feudalism-in-europe |

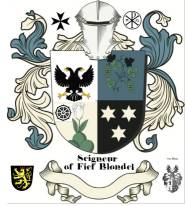

Seigneur de la Fief of Blondel Lord Baron Mentz of Fief Blondel Geurnsey Crown Dependency Seigneur Fief of Blondel George Mentz Lord Baron of Fiefdom Blondel Freiherr of Fief Thomas Blondel Feudal Lord of Baronnie - Noble Fief Barony Friherre > The Feudal System Seigneurs and Dames Travel Research Lord Paramount Feudal Barons The Seigneur Order Patron George Mentz Charter of Liberties Deed & Title Fief Blondel Islands Viking Kingdom Fief Worship Fiefs of the Islands ECS Extended Continental Shelf Styles and Dignities Territorial Waters Blondel Privy Seal Fief Bouvees of Fief Thomas Blondel Guernsey Court of Chief Pleas Fief Court Arms Motto Flower Fief de l'Eperon La Genouinne Kingdom of West Francia Fief DuQuemin Bouvée Phlipot Pain Bouvée Torquetil Bouvée Bourgeon Bailiwick of Ennerdale Channel Island History Fief Direct from the Crown A Funny Think Happened On the Way to the Fief Guernsey Bailiwick of Guernsey - Crown Dependency Confederation des Iles Anglo-Normandes Sovereignty Papal Bull Research Links Norse Normandy Order of the Genet Order of the Genet Order of the Star Est. 1022 Knights of theThistle of Bourbon Count of Anjou Fief Rights Blondel and King Richard Press Carnival Manorial Incidents Appointments of Seigneurs Store Portelet Beach Roquaine Bay Neustrasia Columbier Dovecote Fief Blondel Merchandise Fief Blondel Beaches Islands Foreshore Events Fiefs For Sale Sold Lords of Normandy Fief Coin Viscounts de Contentin Fief Blondel Map Feudal Guernsey Titles Board of Trustees The Feudal System Hereditaments Chancellor Flag & Arms Fief Videos Guernsey Castle Sark Contact Advowson Site Map Disclaimer Freiherr Livres de perchage Lord Baron Longford Income Tax Guernsey Valliscaulian Order Saint Benedict of the Celestines Society of Divine Compassion Dictionary Count of Mortain Seigneur de Saint-Sauveur Seigneur of Fief Ansquetil Top Success Books Datuk Seri George Mentz Order St. Benedict OSB Celestines Order of the Iron Crown Order of the White Falcon Colonel Mentz Order Red Eagle Order St. Louis Order Holy Ghost Order of Saint Anthony Order of the Black Swan Order of St Columban Order of the Iron Helmet Livonian Brothers of the Sword Fief treizième and Direct from Crown Valuation Fief Blondel Prince of Annaly Teffia

Feudal Lord of the Fief Blondel of the Nordic Channel Islands Guernsey Est.

1179

Feudalherr - Fief Blondel von der Nordischen Insel Guernsey Est. 1179

New York Gazette - Magazine of Wall Street -

George Mentz -

George Mentz - Aspen Commission - Mentz Arms

Counselor George Mentz Esq. - Seigneur Feif BlondelBaron Annaly Baron Moyashel Grants to Delvin About Longford Styles and Dignities The Seigneur Court Barons Fiefs of the Islands Longford Map The Island Lords Market & Fair Fief Worship Channel Island History Fief Blondel Lord Baron Longford Fief Rights Fief Blondel Merchandise Events Blondel and King Richard Fief Coin Feudal Guernsey Titles The Feudal System Flag & Arms Castle Site Map Disclaimer Blondel Myth DictionaryMentz Scholarship Program 101 Million Donation - Order of the Genet Knighthood |

George Mentz Education -

Commissioner George Mentz

-

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/commissioner-george-mentz-clinches-influencer-180000705.html

-

George Mentz News -

George Mentz Net Worth - George Mentz Noble Tilte -

George Mentz -

George Mentz Trump Commissioner -

George Mentz Freiherren Count Baron -

George Mentz Global Economic Forum -

George Mentz Donates Millions